The internet loves to poke fun at people who got it wrong, but those ridiculed forecasters might get the last laugh.

This piece was originally published at WIRED.

The incorrect predictions of yesterday have become an entire genre of listicle. There are hundreds, maybe thousands of them online—“The 7 Worst Tech Predictions of All Time,” according to PC Magazine, “15 Worst Tech Predictions of All Time” at Forbes, and “13 Future Predictions That Were So Wrong People Would Probably Regret Saying Them” at Bored Panda, to name just a few. These lists are often hilarious, full of prognostications that to our modern eye seem completely absurd.

Here are a few classics of the genre: “Rail travel at high speed is not possible because passengers, unable to breathe, would die of asphyxia,” said the Irish writer Dionysius Lardner in 1830. “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers,” said the head of IBM in 1943. And “What use could this company make of an electrical toy?” said the head of Western Union about the telephone in 1876. Wrong, wrong, and wrong again.

There’s just one problem: None of those three quotes were ever uttered. In fact, a whole lot of the quotes that litter these popular listicles are either completely fabricated or taken out of context. And the glee with which we invent and soak in failed past predictions reveals a lot about how we think about, and perhaps miss, the real perils lurking on the road ahead.

But first, let us clear the names of a few maligned souls who are endlessly misquoted as fools.

The first time that quote about rail travel suffocating riders appears in the written record is in 1980—and Lardner, the supposed speaker, died in 1859. Lardner did get other things wrong about trains, but they’re far less interesting: He argued with a man named Isambard Kingdom Brunel about the designs for train routes and was often wrong, but his assertions had to do with calculating friction and other things that aren’t nearly sexy enough to put on a listicle.

In fact, in 1830, when Lardner allegedly feared that trains might take our collective breaths away, the locomotives in question went about 30 miles per hour. A horse, at a gallop, goes about the same speed. (Speaking of historically dodgy stories, the idea that a train raced a horse in 1830 seems to be a myth). What he might have actually worried about was asphyxiation within a tunnel—something that actually did happen in 1861, when two men in a tunnel in Blisworth, England, died from the fumes of a steamboat engine.

(This is not to say one can’t find funny and inaccurate predictions about the impact of a vehicle’s speed on the human body. In 1904, The New York Times published a story wondering if human brains were able to think at the speed of cars. “It remains to be proved how fast the brain is capable of traveling,” the author wrote. They worried that at speeds over 80 mph the car might be “running without the guidance of the brain, and the many disastrous results are not to be marveled at.”)

Or take the quote from the IBM head Thomas Watson about there being “a world market for maybe five computers.” Watson’s quote is so ubiquitous in lists of ridiculously bad future predictions that IBM even feels the need to clear this up in the FAQ section of a company history, explaining that the statement seems to come from something Watson said at the IBM stockholders meeting on April 28, 1953. Watson was telling stockholders about the IBM 701 Electronic Data Processing Machine, also sometimes known as the “Defense Calculator.” The 701 was a key step in IBM’s move from punchcard machines to digital processing, and the system’s main clientele was the government and giant science labs.

This is the computer Watson was talking about when he said the following: “I would like to tell you that the machine rents for between $12,000 and $18,000 a month, so it was not the type of thing that could be sold from place to place. But, as a result of our trip, on which we expected to get orders for five machines, we came home with orders for 18.”

So not only was he not making a prediction about the future, he never said there was a “world market for maybe five computers,” and even in the moment he was reporting that, in fact, there was more demand than expected.

Another computer-related favorite is a quote by Digital Equipment Corporation cofounder Ken Olsen at a 1977 talk to the World Future Society in Boston. Olsen allegedly said he saw “no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.” Olsen has been trying to set the record straight ever since that he wasn’t talking about personal computers, but about a computer that could control an entire home—the kind of completely autonomous, fully integrated computer system seen in science fiction of the 1970s (think HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey).

Other times, these so-called predictions are really strategic denials for public relations purposes. Take the telephone—in another oft-repeated example of pessimistic foolishness, the Telegraph Company (the predecessor to Western Union) is said to have turned down Alexander Graham Bell’s patent for the telephone. The exact person who turned Bell down changes between stories—sometimes it's William Orton, other times it’s Chauncey M. DePew—but either way, the company declines, saying things like “This ‘telephone’ has too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication.” In one telling of the story from 1910, Orton says, “What use could this company make of an electrical toy?”

These quotes themselves have been called into question by modern historians, including Phil Lapsley, author of Exploding the Phone, who has tried to track down the origin of the quotation and concluded that “the quote isn’t true. It’s a made-up blend of several different, but related, stories.” On top of that, the idea that the Telegraph Company was shortsighted and failed to see the potential of the telephone doesn’t seem to bear out. The company wasn’t staffed by foolish technophobes; it was run by businessmen. In fact, according to an autobiography by DePew, when the men of the Telegraph Company reviewed Bell’s patent they decided that “if the device has any value, the Western Union owns a prior patent called the Gray’s patent, which makes the Bell device worthless.” Western Union immediately went on to use said patent and create their own version of the telephone.

In other words, the doubt was not in the idea of the telephone, the doubt was whether purchasing Bell’s particular patent was a prudent business decision when they had a similar one of their own.

Perhaps the most popular source of inaccurate and pessimistic past predictions is the Pessimist’s Archive, founded by Louis Anslow in 2015. The project started as a Twitter account and then branched out to a podcast, newsletter and website. It averages about a million views a month and boasts follows from Gwenyth Paltrow to Matt Taibbi.

In the early days of the Pessimist’s Archive, they did accidentally share some of the fakes. He remembers the Alexander Graham Bell one, which got called out on Twitter, leading to a correction. Another time, a different Bell fake got them—the claim that Bell later came to hate his own invention. Now, they stick to published articles in newspapers. “The funny thing about the fake quotes that are floating around is that it is easy to find similar real ones without much effort,” he says. And it’s true—there are plenty of legit and hilariously wrong predictions out there too. Einstein really did think nuclear power was impossible. Lord Kelvin really did think that “X-rays will prove to be a hoax.” People have been predicting flying cars to no avail since at least 1924.

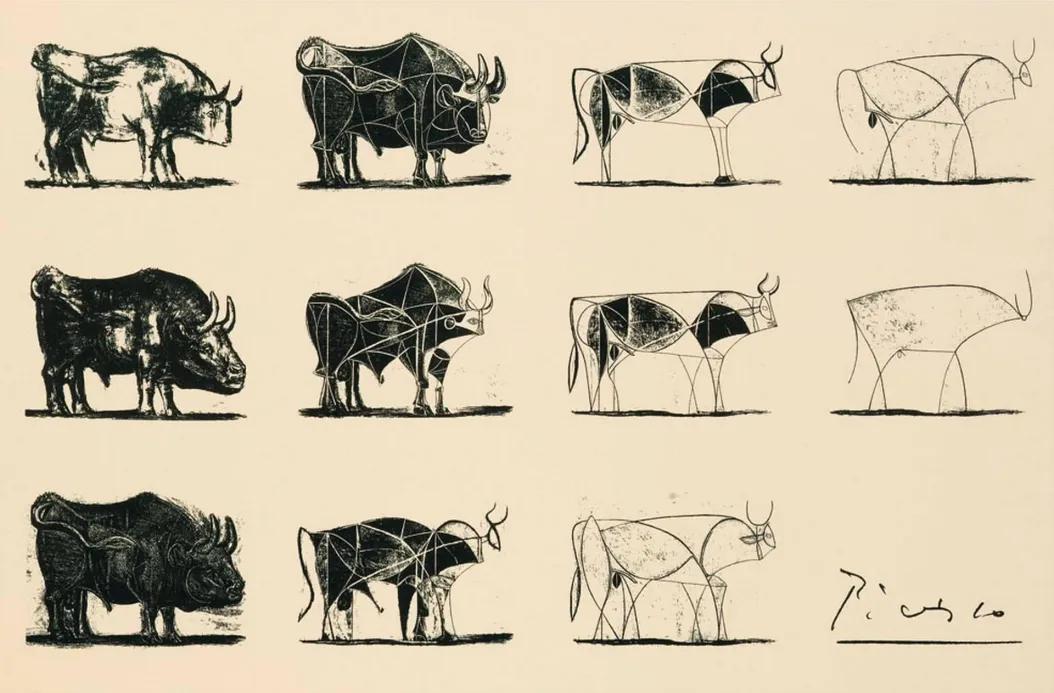

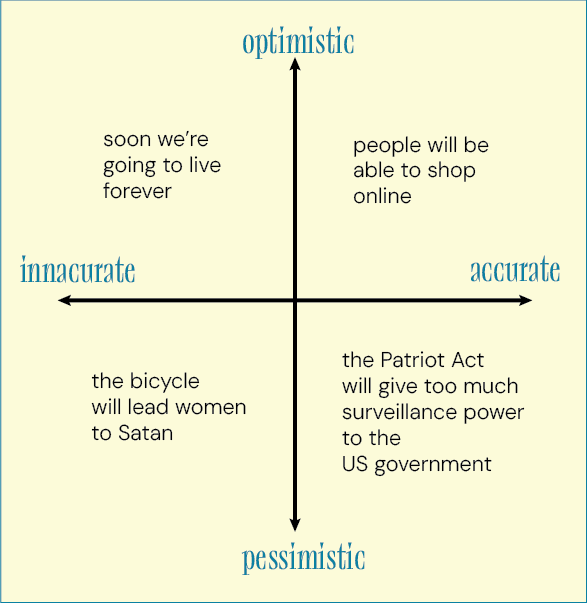

There are all kinds of predictions out there, both good and bad. To organize them, one could imagine a kind of prediction matrix with two axes: accuracy on the x axis (from incorrect to correct) and tone on the y (from pessimistic to optimistic). There are predictions that fall within all four quadrants: inaccurate and pessimistic (the bicycle will lead women to Satan), inaccurate and optimistic (soon we’re going to live forever), accurate and pessimistic (US senator Russ Feingold’s prescient objection to the Patriot Act, warning that it gave far too much surveillance power to the US government), accurate and optimistic (Philco-Ford predicting online shopping in 1967 (though they called it “fingertip shopping”).

But the predictions that populate the “worst predictions of all time” compilations are of a very specific flavor—they all occupy one quadrant of our matrix. Nearly every one of the entries on these lists reflects a skepticism toward new technologies that is later proven wrong. “It involves cherry-picking,” says Lee Vinsel, a professor of science and technology studies at Virginia Tech and the coauthor of The Innovation Delusion. “Because it's not talking about drugs that ended up causing birth defects and got pulled from the market, or all the deaths that come from automobiles. I think we could create an alternative list of things we’ve introduced that we realize are harmful and then have to figure out how to deal with.”

Often, these lists are arguing that our past is littered with skepticism toward new technologies, some of which wound up being positive or at least ubiquitous in our lives. They come with the implicit (and sometimes explicit) framing that skepticism of technology is foolish, and that by extension, today’s skeptics will look just as silly as the buffoons of the past. “Although people often fear the future, overall it keeps on getting better for one reason: Evolution … Everything is constantly evolving, improving and getting better,” writes one listicle author. Or as Vinsel says: “The message these folks want to push is that entrepreneurship and technological change are good and are mostly benefits to society.”

These lists also provide a nice buffer of plausible deniability for those in the field of inventions and future thinking. At the end of one such list, a company called Hero Labs puts it this way: “That’s why we’re always prepared to tear up the rule book and never afraid to admit when we’re wrong. If anyone complains, we can just show them the list above!”

Both Anslow and Jason Feifer, who hosted the Pessimist’s Archive podcast (which has since split off as its own independent podcast called Build For Tomorrow) are unapologetically pro-technological acceleration, but they have slightly different takes on the true message of these failed predictions. For Anslow, the big lesson he takes from the Pessimist’s Archive is to reject stagnation. He argues that skeptics tend to overstate the theoretical risks of adopting new technology, and don’t always consider the risk of waiting. “We shouldn't fear the new, we should fear the old,” he argues. “We should fear stagnation.” For Feifer, it’s more about oversimplification—the idea that skeptics tend to heap every problem into one, unified rejection rather than understanding the nuances of a technology’s potential impact. ”Blaming some new piece of technology for a much broader, more complex problem does not get you to a solution,” he says. “It does the opposite of that. It moves you away from the solution.”

But if the problem is oversimplification of complex problems, then a site that compiled overly simplistic and optimistic predictions would be just as valuable. When I asked why the Pessimist's Archive doesn’t include incorrect but optimistic predictions, Feifer said that in his opinion “overly optimistic takes don't tend to drive media narratives, they don't drive moral panics, they don't drive legislative action.” Perhaps this is true to a degree—most moral panics are driven by fear, not hope. But there are plenty of media narratives driven by hope (see: Theranos, Uber, most of WIRED's early history) and plenty of bad legislation driven by naive optimism (see: the idea that simply giving the police more money will solve the problem of police violence).

And there is obviously danger in over-indexing the positive predictions too. In a recent essay, historian David Karpf writes, “Throughout my adult life, tech optimism has been the dominant paradigm … Along the way, we have stopped regulating tech monopolies, we have reduced taxes on the wealthy, we have let public-interest journalism wither, and we have (until oh-so-recently) treated the climate crisis as a problem for someone else, sometime later. The most powerful people in the world are optimists. Their optimism is not helping.”

And while some of these botched prediction lists can be fun to read, giving too much weight to the value of inaccurate forecasts can easily be weaponized. Take, for example, climate change. In certain arenas of the internet, there are memes poking fun at Al Gore for predicting that there might not be any ice left in 2022. The Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank, publishes a list called “Wrong Again: 50 Years of Failed Eco-Pocalyptic Predictions.” Some of these predictions are just as wrong as the ones that grace the Pessimist’s Archive. In 1970, a scientist quoted by The Boston Globe predicted that “the demands for cooling water will boil dry the entire flow of the rivers and streams of continental United States,” and that simultaneously “air pollution may obliterate the sun and cause a new ice age in the first third of the next century.” The subtext is that because none of the things happened, the threat of climate change as a whole is clearly overstated.

But of course we know that isn’t true. Just because people got things wrong about climate change in the past doesn’t mean the problem isn’t real, or that the forecasts of future warming should be ignored. Vinsel sees this problem all the time in historical analysis. “People are reading what we know now back into the sources and not really thinking about how those people are looking at the world and what they're contending with.” Exploring why people got things wrong is useful not simply for the fact of the wrongness, but for exploring what they missed. We should learn not from their collective skepticism, but from their specific worries and what they didn’t understand about the science or technology or culture at play.

And the way that some list lovers reduce these disparate predictions across centuries and from a wide variety of contexts into a bigger, broader lesson about progress and its inevitable goodness, removes any real specific lesson we might learn from these past predictions. Take the Y2K non-disaster for example—another oft-included item on lists of incorrect predictions. It’s true that the world didn’t shut down on January 1, 2000, but that’s not because the concern was misplaced. It’s because thousands of people worked overtime to patch the system and solve the problem. Or take the failed predictions of city planners in Los Angeles who said the city would have a world-class public transit system in the 1940’s, so people wouldn’t have to drive their fancy cars everywhere. They were wrong not because public transit was inferior to cars, but because General Motors bought up all the rail lines and ruined them.

As always, the best method for evaluating which predictions to pay attention to is the most laborious: look at each one individually and prioritize the evaluations that engage with the most specific context for that particular piece of technology. And we should remember that learning from the past is certainly worthy, but not every modern problem has an exact historical ancestor. (“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes,” is a quote that both Feifer and Anslow referenced when we spoke—a quote that, ironically, has often been misattributed to Mark Twain.) A friend once called this “the genealogy of ideas problem”—that the desire to find that historical precedent reduces for many to finding a historical precedent for something modern, and in doing so reduces a problem or issue down to only the constituent parts that link back to something in the past. This desire suggests that nothing is truly new, that no issues today have nuances that our historical counterparts haven’t seen, and that we can learn this lesson once, in aggregate, from all our past failures of imagination.

It’s easy to be wrong about the future in all kinds of ways—hopeful, pessimistic, and everywhere in between. Maybe this is because “the future” itself is not just one thing, not a single event or variable or even a single feeling or path. The future contains hope, pessimism, and everything else in between. Sometimes things that seems wrong at the time turn out right for strange reasons. Sometimes things that seem reasonable in the moment have wide-ranging impacts nobody could have foretold. Because of that, perhaps we should spend less time on sweeping, dramatic predictions pointing to a singular, flattened, and evenly distributed future, and more time with the details of how a specific technology might impact specific people.

We cling to predictions because of their air of certainty, but predictions are most useful when they provide contours and specifics, when they leave room for nuance and flexibility and possibility. Rather than announcing that artificial intelligence will become sentient and rule us all, we should examine the various applications of AI and how they might impact communities and people that exist today. We should ask who is funding a project, who owns it, how it’s been trained, and how it’s being deployed. Prediction is not futile, but zooming in instead of zooming out is where the real insight lies. Sure, even the most well considered predictions will still turn out wrong much of the time. But if they help us think through our choices and move towards a better, more humane world, maybe being wrong is OK.