This blog post was originally sent as a newsletter to members in August, 2023.

I am personally fascinated by process stuff. Perhaps too fascinated. I can be easily convinced that spending a whole day reorganizing my notes into a new, better, more visually pleasing way is actually work. (I think a lot about this old post by John Pavlus about being a recovering life hacker.)

You can find a hundred thousand posts from people arguing that their process is the superior one, and guides for how to follow them into productive bliss. There are whole books about how certain ways of doing things are allegedly backed by science, or will produce a story that is commercially viable, or will save you time. There are books about how to think about creativity, and how to structure your day and weekly creative output to unlock your potential.

This blog post is not any of that. This isn’t a tutorial or a pitch or a guide to how to do things my way. My process is certainly not the best one, and it’s ever-evolving. But I thought it might also be interesting to see how I organize my notes and thinking around a few projects?

I recently switched all my writing from Scrivener to Obsidian. I know many people love Scrivener, and there are a hundred thousand guides and YouTube videos and explainers on how it works and how to make it work for you. I could never quite get my brain to click with it.

Obsidian, on the other hand, makes sense to me. And, of course, there are probably even more guides and YouTube videos and explainers on how Obsidian works because it’s a piece of software that has attracted a lot of techy people who love documentation and efficiency.

The thing I like about Obsidian is that I can link thoughts and ideas and notes together in a way I could never quite figure out with Scrivener. This makes my magpie research gathering much easier to synthesize from, and it makes it easier for me to always know where various things have come from.

I now use Obsidian for both non-fiction and fiction, so let’s start with non-fiction because it’s a little easier to show some of the interesting stuff that is possible with Obsidian.

NON FICTION

For my non fiction book project (which is still in the proposal phase), one of the big things I’m doing is reading a ton of texts about everything from eschatology in the Middle Ages to the psychology of time to the history of almanacs. Most of these books come from the library (fun fact: any California resident can get a library card to the University of California campus near them) and I take notes on them into a reMarkable tablet.

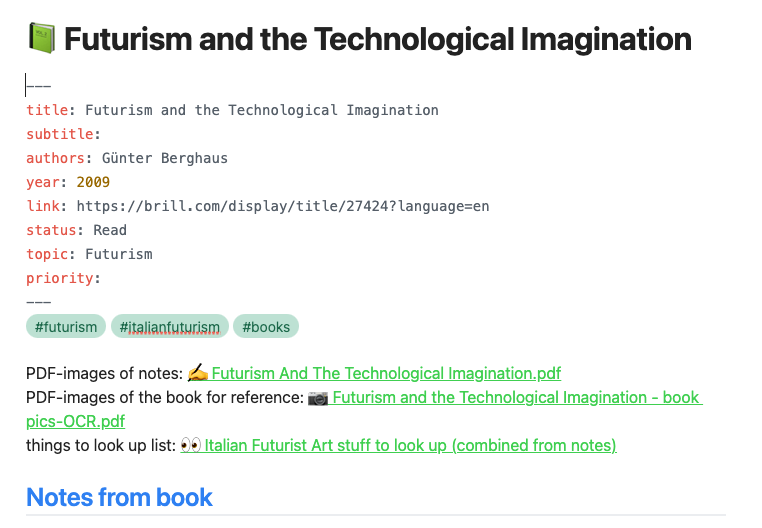

Each book then gets its own little note in Obsidian (linked to my Zotero to keep track of citations), which I tag with a variety of meta-data to keep track of things. And as I take notes, I also note something that I want to look up more about with a little 🧿 emoji. So here is what a note looks like for a book:

Within those notes, I can also tag things that connect to something the author is saying, and it will connect to the note I have on that idea. So if, for example, Berghaus writes something in this book about the ways in which Italian Futurists play with concepts of time, I can tag [[concepts of time]] which will create a link to my note about that thing.

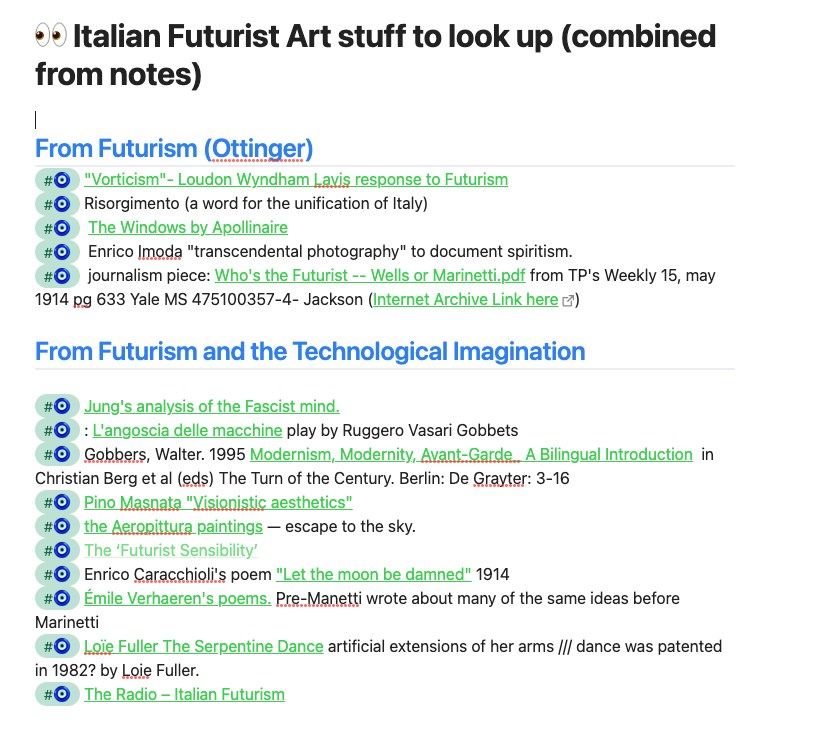

Once I’m done with the notes for a book, I compile anything with the 🧿 emoji into a list — for this book/topic area that looks like this:

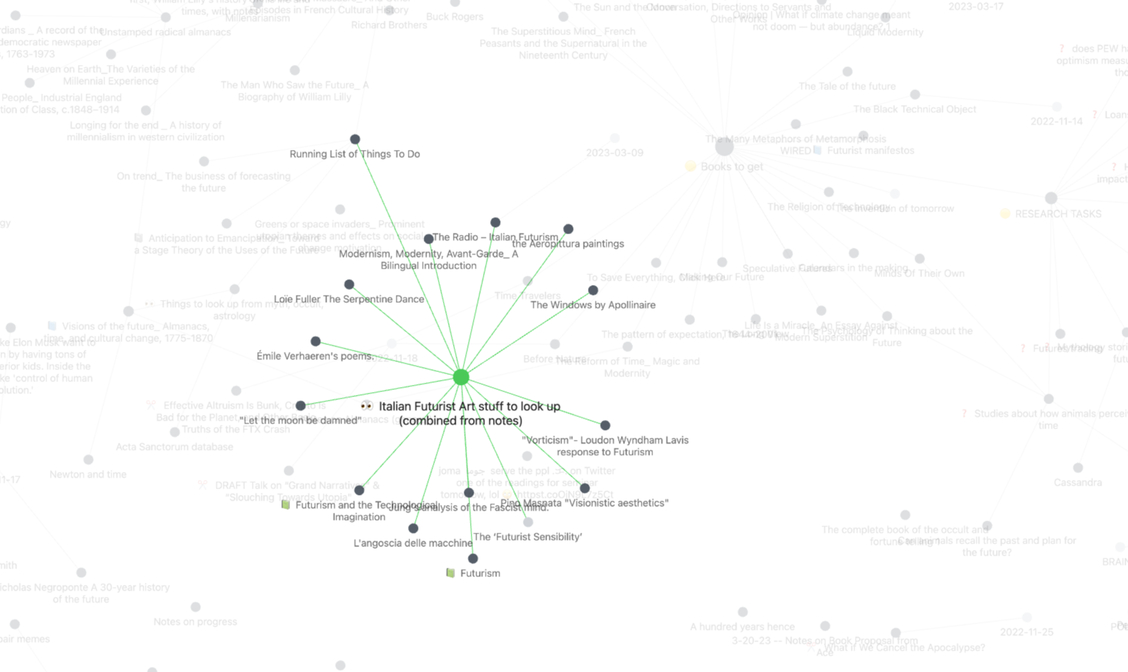

Each of those little green bits of text are clickable, and take me to a new note about that thing. And in Obsidian it tracks all these connection points. So you can see how various ideas are linked up:

There are a ton of things you can do with Obsidian if you’re well versed in code and such, which I am not. The whole premise of the system is to be a platform on which people build things, and people have come up with all kinds of cool and interesting (and to be honest, sometimes quite fiddly) things you can do with this. If that intrigues you, by all means check out the Obsidian Discord where people are chatting all day about the various stuff they’re building.

FICTION

I also use Obsidian for fiction writing, and a lot of this stuff applies to fiction too, particularly around organizing my research. But one of the other nice things about writing in Obsidian is that it makes it easy to keep track of versions, and where things are. So here is a note from the novel I’m working on:

Using this metadata I can track where each chapter and scene is and what it needs, as well as keep track of characters and point of views.

When writing fiction there are a few other documents that I always generate for each story or project:

VIBES — a document with keywords, images, and a playlist to write to.

PLOT — a fairly detailed plot outline (I am a plotter, I need to know where a story is going before I can write).

NOTES — a long, running document with stream of consciousness stuff, notes from my morning pages, whatever else comes to mind.

CHARACTERS — as it sounds, a detailed breakdown of the backstories of my characters, some of which makes it into the story and some of which doesn’t.

RESEARCH — a master doc of all the various research questions I have about the world, the people, the time period.

JUNK PHRASES — see below for more on that from Monica Byrne.

EDITING NOTES — an ever evolving list of things I know I need to fix on the next edit.

I also keep a few general notes constantly running — mostly to write things down that I hear, or ideas I have that I think could be useful in the future. No idea is too big or small or weird. For example, I currently have the following in this document:

It’s when you’re walking and you’re looking out at the lake and you notice that the shadows the cars are making on the lake kind of like ducks but then there are also real ducks and then you wonder if the real ducks ever think the shadow ducks are real ducks and talk to them.

Who knows, maybe that will be a useful thought in the future for something.

I drop in paintings, poems, random links, everything.

This is the second version of Caravaggio’s painting “The Fortune Teller” (circa 1595) and it’s become symbolic to me because oddly enough two of my projects right now about about versions of fortune telling that are both captured, in their own, very different ways, in this painting. In 1603, the poet Gaspare Murtola wrote a madrigal (a short lyric poem designed for multiple singers) about this painting that I think about a lot.

I don't know who is the greater sorcerer

The woman you portray

Or you who paint her. Through sweetest incantation

She doth desire to steal

Our very heart and blood. Thou wouldst in thy portrayal

Her living, breathing image

For others reproduce, That they too may believe it.

When he painted the first version of this painting, Caravaggio was in a tight spot financially, and he had to sell it for just eight scudi (it's hard to make exact conversions for this kind of denomination but my understanding is that that's about $200). A year later, a wealthy Cardinal named Francesco Maria Del Monte bought another piece by Caravaggio that was a companion to The Fortune Teller. Del Monte didn't want to only have one half of the set, so he asked Caravaggio to paint a new copy of The Fortune Teller for him. And when you're an artist trying to make money, you paint the new version.

A few more interesting things to read about process

- Junk phrases by Monica Byrne. (Only available to subscribers)

- How to write things fast part one, and part two

- Never Say You Can’t Survive by Charlie Jane Anders

- Some Thoughts on Short Story Endings

- The Artist’s Way (I know this is cheesy but I love it)

- How Lydia Kiesling created her own writing residency

- Take Off Your Pants! Outline Your Books for Faster, Better Writing by Libbie Hawker