What does it mean to sustain a creative life right now?

For the last ten years, I've cobbled together an income from freelance jobs, crowdfunding, and the occasional talk or workshop. There were times when all I had was support from a small but loyal group of podcast listeners. There were times I piled gig on top of gig, to save up money to fund the leaner times. Throughout it all I slowly built up a safety net— scrapping and saving and taking on silly little blogging jobs, editing projects, consulting gigs, and always (always) riding the bus.

I thought maybe I'd use those savings on a downpayment for a house. Or keep them for a rainy day, or an unexpected illness, or a future kid.

In July I published Tested, a project I had been pitching for eight years, and researching for ten. I was lucky enough to work with two huge outlets on the show — CBC and NPR. But the reality of today's podcast market and media budgets is this: the money they could spend on the show was not the amount of money the show cost to make. So instead of spending that nest egg on a house, I spent it on a podcast.

My only income at the moment comes from members of my membership club – which until recently was centered around my old podcast Flash Forward. I launched the membership thinking that I would use the money to create a podcast studio, making shows about the future. When I launched Flash Forward Presents, I wrote:

In 2015 I founded a podcast called Flash Forward. Eight years and nearly 200 episodes later, my curiosity about the future hasn’t waned, nor has my belief that helping people imagine what might be coming has real, tangible benefits. And to help people do that imagining, I’ve branched out from Flash Forward to a handful of other creative endeavors which all live under this new umbrella of “Flash Forward Presents.” Basically this is the Flash Forward Extended Cinematic Universe.

Over the past two years I've realized that this isn't quite right for me anymore. I don't want to just make work that is pinned to Flash Forward as the starting point. So I'm shifting a little — not quite a pivot, exactly, but putting a new lens on what I was already doing that should help folks see the work a little more clearly.

I have lots of projects and ideas I'm exploring. Some of them I might be able to sell. But the madness of freelancing is that there are long stretches of time where you have to do a whole lot of work hoping that there's money on the other end of the rainbow. And so I'm shifting my membership club a little bit to try and focus less on the past (Flash Forward ended years ago now) and more on the present and potential future of my working life.

What the heck is "cardiac serpent?"

It's a bit of a long story, but I think that perhaps tracing the story of the name is a good indicator of what you can expect in terms of how I think.

In 2018, I wrote a blog post for the group blog Last Word on Nothing about ideas. I wrote about how I actually don't really lack for ideas. I believe that having ideas is easy — it's actually figuring out if they're good ideas and then how to execute on them that's hard. Here's what I wrote in 2018:

For me at least, ideas are often like glow sticks. You know the kind you have to break and shake to make glow? They only glow for a certain period of time. After a while, they fade, and become dull plastic sticks that I’m gathering in a pile in the corner of the room.

At the time I wrote this blog, I was waterboarding myself with books about creativity. I had all these ideas but was paralyzed with how to execute on them, what to do, which glowsticks to break, and how. There is a famous book called The Artist's Way by Julia Cameron that talks a lot about where ideas come from. For her, it was God. “Remembering that God is my source, we are in the spiritual position of having an unlimited bank account,” she writes. But for me... well... I'm not that into the whole God thing.

But I still wanted to visualize something. To imagine my source of ideas as something physical. Something I can picture.

In another book on creativity, Elizabeth Gilbert writes about a poet named Ruth Stone. Stone describes her ideas as more of a feeling. Here's how Gilbert describes it:

It was like a thunderous train of air and it would come barrelling down at her over the landscape. And when she felt it coming . . . ’cause it would shake the earth under her feet, she knew she had only one thing to do at that point. That was to, in her words, “run like hell” to the house as she would be chased by this poem.

The whole deal was that she had to get to a piece of paper fast enough so that when it thundered through her, she could collect it and grab it on the page. Other times she wouldn’t be fast enough, so she would be running and running, and she wouldn’t get to the house, and the poem would barrel through her and she would miss it, and it would “continue on across the landscape looking for another poet.”

And then there were these times, there were moments where she would almost miss it. She is running to the house and is looking for the paper and the poem passes through her. She grabs a pencil just as it’s going through her and she would reach out with her other hand and she would catch it. She would catch the poem by its tail and she would pull it backwards into her body as she was transcribing on the page. In those instances, the poem would come up on the page perfect and intact, but backwards, from the last word to the first.

"She would catch the poem by its tail" really grabbed me as a literal, visual image. In some accounts writers say that Stone is talking about a tiger's tail — but I could never find any specific reference to a tiger from Stone herself. But something fleeting, something wiggling, something long and winding.

This image made me think of eels, I guess because tiger tails, unattached from their feline bodies, are quite eel like. And because I am never one to shy away from an extended metaphor, I ran with it.

Here's how I explained it in 2018:

The barrel of slimy, glowing eels has always been inside me. The eels feed on the ideas and art I take in, read and experience. They grow and mate in this barrel, like a disgusting soup. A disgusting soup that I rely on for my livelihood. I must take care of my barrel of slimy, glowing eels, and be sure not to break the container so they all escape. But I do want to carve out a doggy door (eel door?) so that they can get out, and back in I suppose. Perhaps I have to take a woodworking class to carve this doggy/eel door and to best care for these eels (this would be some kind of professional writing classes or training, in case you’re not following my fucked up metaphor).

I have to train myself on the most effective eel catching methods, too. How does one catch eels? Bare handed? Do I design myself some gloves? Or some kind of hunting stick, or camera trap. Maybe I should sing to the eels, to make them feel safe. I need to become an eel expert, to be able to tell which are healthy and which are sick and need attention, and which should be let go. Some eels are not meant for my barrel.

This is why my personal newsletter has been called Bucket of Eels, as is my production company — the one that made Tested and other non-Flash Forward shows. I have an LLC that bears that name, and even a credit card that says "Bucket of Eels" on it. (I confess I did not think about having to say "produced by Bucket of Eels" on a show that millions of people were going to listen to.)

I could have left it there, and just converted the membership club around the Bucket of Eels brand. And maybe that would have been the smarter move. But that's not what I've done.

Eels are my favorite animals, and so sometimes when I'm looking to waste a little bit of time on the internet, I'll google "eel" and some other thing. "Eel" mythology. "Eel" conspiracy. "Eel" sports.

And on a recent little google foray, I came across this blog post called "A Monster in the Heart: Edward May’s A Most Certaine and True Relation (1639)" on Public Domain Review.

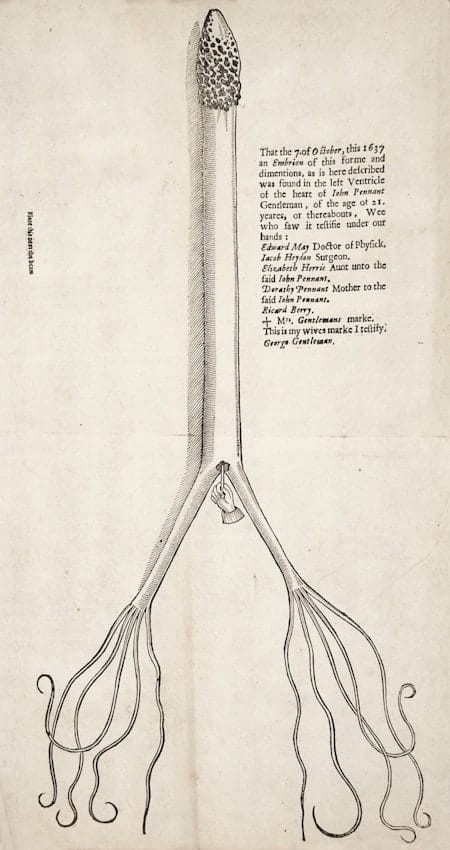

The post dives into a small section of a very old book written by a physician named Edward May. May describes an experience in which he was called to do an autopsy on a twenty-one year old man who died unexpectedly. The investigation found all kinds of things, but in particular noted that the man had an eel in his heart. A "carnouse [fleshy] substance. . . wreathed together in foldes like a worme or Serpent."

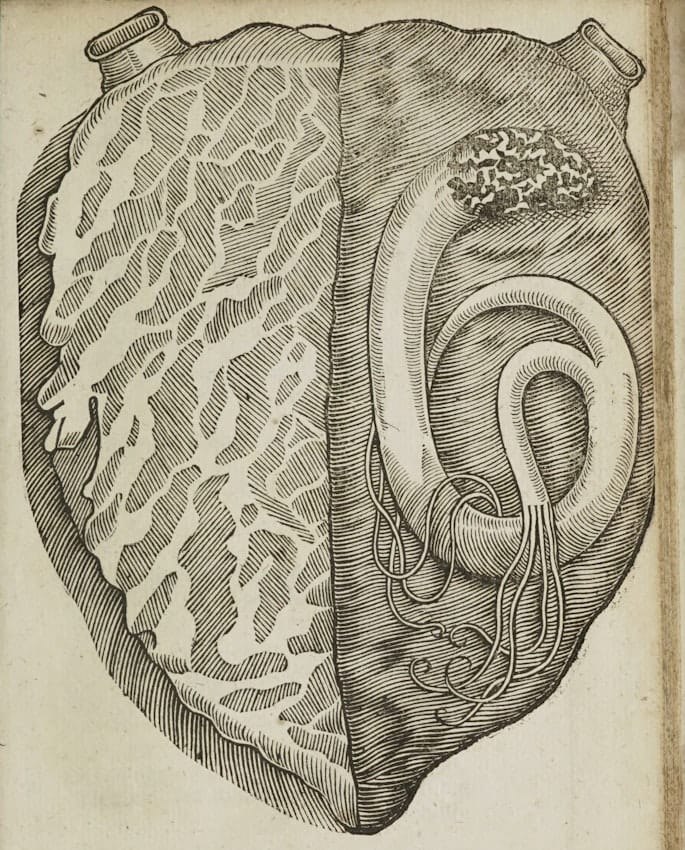

The account comes with two incredible images.

May recounts not only this very strange finding, but also the impact that he believes it had on Pennant's life — namely that the man had somehow absorbed the qualities of the serpent. He writes that the victim had "an excellent Eye" that was “like the Eye of a Serpent." Here's Hunter Dukes, writing in Public Domain Review:

... which leads May to an affirmation of what is known as the doctrine of signatures, a belief that proximity engenders resemblance: “secret, unusuall and strange inward diseases, doe send forth some radios, or signatures from the center”. He hopes that these signatures might be recognized by other physicians before serpents kill their patients too. As for this particular monster, it was sewn back into Pennant’s corpse, honoring Dorothy Pennant’s wishes for her son: “As it came with him, so it shall goe with him”.

For his part, May was furious at Dorothy Pennant over this. He wanted to keep the serpent to study and parade around to his fellow doctors. He even ranted about her "ignorance" and "sugar-sop . . . babish . . . Cockney disposition" in his account.

For centuries this finding has been a bit of a mystery to medical historians and researchers. There was at one point a theory that May had found a type of heart worm that generally only impacts horses. But several researchers in the last few decades have rejected this idea. In 2001, a paper by Ruth Richardson published in The Lancet argues that "Most likely, the serpent was clotted plasma."

I'm not sure I can fully articulate why this story grabbed me so much. Maybe it's just that "cardiac serpent" is a really cool phrase (and a great band name). Maybe it's the combination of medical history and fun little mystery. Maybe it's the mother who rejected a medical man's pompous desire to turn her son's body into a spectacle. Maybe it's the illustrations — the little hand pointing into the limbs of the serpent. What would it be like to have an eel in your heart? If my ideas are eels, then I suppose that's where some of them live.

And so here we are. Cardiac Serpent. A new era, a new name, a new incredibly convoluted and extended metaphor.

What is membership anyway?

I've had some form of direct support going for a long time now. Flash Forward was launched and sustained through Patreon. Even before that I ran a Kickstarter for a now defunct project called Science Studio. But the ways I've been thinking about direct support — what it means, how to do it, and what it could look like — have changed a lot over the years.

As part of my thinking about this new phase of funding my work, I've been reading a lot about what a creative economy (big and small) looks like these days. I take a lot of inspiration from Erin Kissane, who wrote that along with needing the support to keep doing the work, she also wants "to know that there are real people who value this work enough to make it worth continuing even when it's hard and weird." Craig Mod calls this "permission."

To get that kind of support, community, permission — that's the trick. The hard part. The mysterious thing that everybody I know seems to be trying to figure out. It requires a personal brand. It requires content. It requires some kind of regular output, preferably on a bounded and enticing topic, probably in the form of a newsletter. If you're really good, it includes some kind of engagement.

"The internet has made it so that no matter who you are or what you do — from 9-to-5 middle managers to astronauts to housecleaners — you cannot escape the tyranny of the personal brand," writes Rebecca Jennings. "You’ve got to offer your content to the hellish, overstuffed, harassment-laden, uber-competitive attention economy because otherwise no one will know who you are."

Back in 2015, William Deresiewicz observed this already happening. "But one of the most conspicuous things about today’s young creators is their tendency to construct a multiplicity of artistic identities," he wrote in The Atlantic. "You’re a musician and a photographer and a poet; a storyteller and a dancer and a designer—a multiplatform artist, in the term one sometimes sees. Which means that you haven’t got time for your 10,000 hours in any of your chosen media. But technique or expertise is not the point. The point is versatility. Like any good business, you try to diversify.” Or, as Ann Helen Petersen wrote recently in a newsletter considering complaints about "kids these days" in journalism: "Their “work ethic” was the result of market dynamics: work like this or don’t work at all."

If you do it right, you might make a living wage. "We’ve been cored like apples, a dependency created, hooked on the public internet to tell us the worth," writes Thea Lim. "The market is the only mechanism for a piece of art to reach a pair of loving eyes. Even at a museum or library, the market had a hand in homing the item there."

Here's on small example of how this shows up for me: When I left Twitter a few years ago, my first worry wasn't my friends or the cute memes or important news stories I might miss. It was that it would be harder for me to sell a book without a platform.

Meanwhile, there is also a lot of healthy discussion about parasocial relationships. Chappel Roan has been pushing back on fan demands of her time and attention. This has been an ongoing conversation across many mediums for years — and it's something people have been talking about in podcasting for a long time. More so even than fans of giant pop stars or actors, podcast listeners feel like they know the hosts of these shows. But of course, they don't. And podcasters too have started setting boundaries and pushing back.

When you're funded directly by members, this all gets tricky. Because you're no longer simply in a fan/creator relationship. You're now in a fan and financial supporter relationship. The relationship isn't simply "you see my work and like it" it's "you fund my work" and that is a different kind of thing. In the past, I've been really paralyzed by this knowledge. I've spent a lot of time fretting about whether my members will want this or that, whether my pivots on my career are going to work for them, whether they're going to be annoyed if I start talking about something else. For example: when I started working on Tested, I was worried that members of my Flash Forward Presents club would be annoyed that I was no longer doing something about the future.

Where does all of this leave me, personally?

I think it means a couple of things. It means that I have to swallow my discomfort about making something about me and just get over it. And in doing so — in shifting away from a membership that is focused on a specific genre or project — it frees me up to actually let go of some of the worries that I had about whether I was doing the right thing with my time. If you're signing up to support me, Rose Eveleth, you're doing so because you want to support me, Rose Eveleth. Not a project. Not a podcast studio. Not a set of specific rewards. But a person.

What that means in practice is that this new phase of the membership program will be less about rewards (stuff that only members get) and more about support (hoping that there are people out there who are interested in having a small role in funding creative media) and, in Craig Mod's terms, permission.

What are you giving me permission to do? Here are some things on my list:

- Write novels and short stories.

- Make abstract sculptures.

- Work on a non-fiction book proposal.

- Write a screenplay.

- Continue work on ongoing projects like Tested.

- Take classes like welding, glassblowing, basketweaving and more.

- Blog about everything from volleyball to why I sometimes cry in museums.

- and whatever else pops into my head.

Cardiac Serpent

An eel in the heart

stories // sculptures // surprises

Join me?